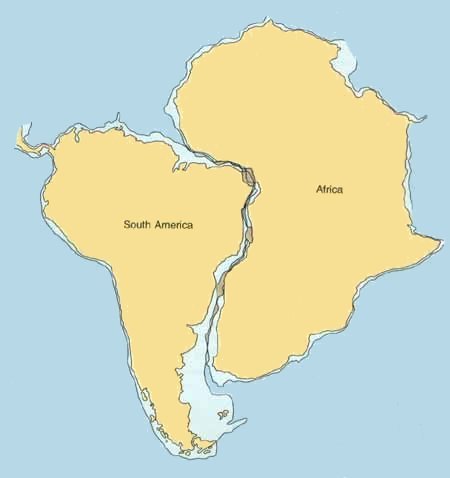

The fit of South America and Africa, including the continental shelf at a depth of 500 metres.

Almost as soon as the continents were mapped, it was noticed that South America fits neatly into the corner of Africa.[1] This fit is even better if you include the shallow underwater shelf which extends around their coastlines.[2]

Is this just a coincidence or were the continents really once joined? Why did they separate? And what is the mechanism that pushed them apart to their current positions?

Answers to these questions[3] were only found within the last fifty years and revolutionised our understanding of the planet: not only does the surface of the planet move, but its movement has had a huge influence on both the climate and the evolution of life.

The cartogapher Abraham Ortelius suggested in 1596 the possibility that the continents had drifted apart to their current positions.

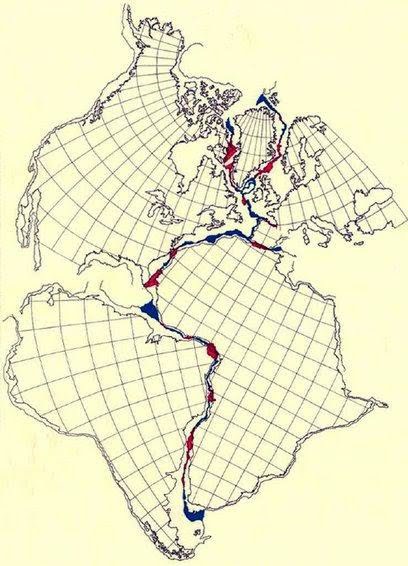

A map of fossil distributions across the continents. These form continuous areas if the continents were once joined together into the super-continent of Pangaea, around 250 million years ago. Map based on Snider-Pellegrini and Wegener.

Snider and Pelligrini gathered fossil evidence in 1859, which showed that fossil distributions made more sense if the continents were once joined together into a super-continent later known as Pangaea (see picture). The fossil distributions now join up like a jigsaw puzzle.

Most geologists did not except this evidence, and assumed that the fossil distribution across the continents could be explained by land bridges which have since disappeared. Examples of such land bridges are the Bering land bridge between Asia and America which is exposed during ice ages and thus allows the transmission of plants and animals across seas too wide to swim or float.

In the 19th century the naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace had studied the differences in living flora and fauna across the 35km of water between the islands of Bali and Lombok in the East Indies. He concluded that the differences between the two sides of what became known as the Wallace line must be because the islands had moved over geological time from a position where they were far apart.

In the 20th century Alfred Wegener picked up on the fossil work of Snider and Pelligrini and added to it evidence from glacial deposits from a mass-glaciation over Gondwana 300 million years ago, along with extensive matching of the age, type and structure of rocks on either side of the Atlantic. He published his Pangaea hypothesis in 1912 [Wegener, 1912].

Only in 1950s was a mechanism for ocean spreading given, following surveys of the ocean floor, and since then much evidence has been amassed.

Including North America in the jigsaw puzzle. Blue and red areas indicate the mismatch: blue for bits that need to be filled in and red for overlaps.

You can include North America in this jigsaw puzzle and the fit with Africa and Europe is also extraordinarily good. This fit was done with the aid of a computer by Edward Bullard of Cambridge University and colleagues in 1965 [Bullard et al., 1965].

There were also other questions that puzzled scientists. For example, rivers dump huge quantities of sediment into the oceans every year. If the Earth's surface is completely static, why hasn't this sediment filled up the oceans by now?

[Bullard et al, 1965]: Bullard, E., Everett, J.E., and Gilbert Smith, A., "The fit of the continents around the Atlantic", in P.M.S. Blackett, E. Bullard and S.K. Runcorn (eds.), "A symposium on continental drift", 1088: 41-51, Royal Society of London, Phil. Trans. (1965).

[Wegener, 1912]: Wegener, Alfred, "Die Entstehung der Kontinente", Geologische Rundschau 3 (4): 276-292 (1912). Translated into English in 1915 as "The Origin of Continents and Oceans".

Author: Tom Brown

Copyright: public domain

Date last modified: 11th Oct 2011

Peer-review status: Not yet peer-reviewed

Fit of continents: source: http://geology.uprm.edu/Morelock/1_image/platfit.jpg, copyright: unknown, has been retouched by TomB

Snider-Pellegrini and Wegener fossil map: source: Wikipedia, copyright: public domain

bullard.jpg: source: [Bullard et al., 1965], copyright: unknown